City Builders and Contemporary Urbanism

How 'SimCity' and 'Cities : Skylines' Depict the Status Quo

Did you know 19th century London almost had a giant, glass roofed, covered arcade which would have looped 18 kilometres around the entire central city? Or elaborate Roman inspired terraces along the Thames? Or 90 story high mausoleum pyramids to house its dead? In historical records there exist countless versions of the great city that never came to be. And not just London, but all the cities of the world. Did you know that it was semi-satirically proposed to dome Manhattan? To reinvigorate Moscow with horizontal skyscrapers? To convert a huge chunk of central Paris into parkland?

So much modern urbanism is shaped by what wasn’t done as much as by what was. Cities are possibility spaces. Places of near endless potential. It’s this that makes them such fruitful concepts for creative videogames, and why its telling that when Will Wright realisied that it was often more fun to build than to destroy, he applied that revelation to a game about building cities first.

And despite city planning being a whole, complicated field of university study (along with traffic engineering), those games depicting this job are amongst the most successful ever released.

Why Critique City Builders?

City building videogames and their ilk are amongst the best selling and most widely played games ever made. The big players, Maxis’ long running SimCity series and Colossal Order’s upstart show stealer Cities: Skylines, have huge followings and dedicated online communities. For those of us who grew up in the 90s, SimCity was the face of “acceptable” gaming. Creative, non-violent, borderline educational, it was the kind of game that you didn’t have to put much effort into selling your parents on. Their appeal crosses generations. My Boomer mother played and enjoyed SimCity 2000, while my 14 year old Zoomer cousin is now big into Cities; Skylines. There is a fundamental excitement to the idea of laying our your own city that makes these types of games instantly appealing to almost everyone.

Of course, what that also means is that it’s important that we understand the assumptions and biases that the developers brought to these games, because these are likely to rub off on us while we play them.

Descriptivism VS. Prescriptivism: How Are City Builders Built?

City builders are not philosophically or politically neutral. This great piece by Clayton Ashley, for example, examines the urbanist theories that underpin SimCity 2000 and calls into question some of the presuppositions that they bring to the “simulation”. These games rely on simplifications and abstractions of complex systems and processes to present plausible representations of urban development, that also must work as a real-time videogame rather than a university supercomputer study. When those simplifications and abstractions are made, biases or misunderstandings from the developers, or their source models, slip in. A key element in understanding what those biases are is to ask “how does this game understand the functions of a city?”.

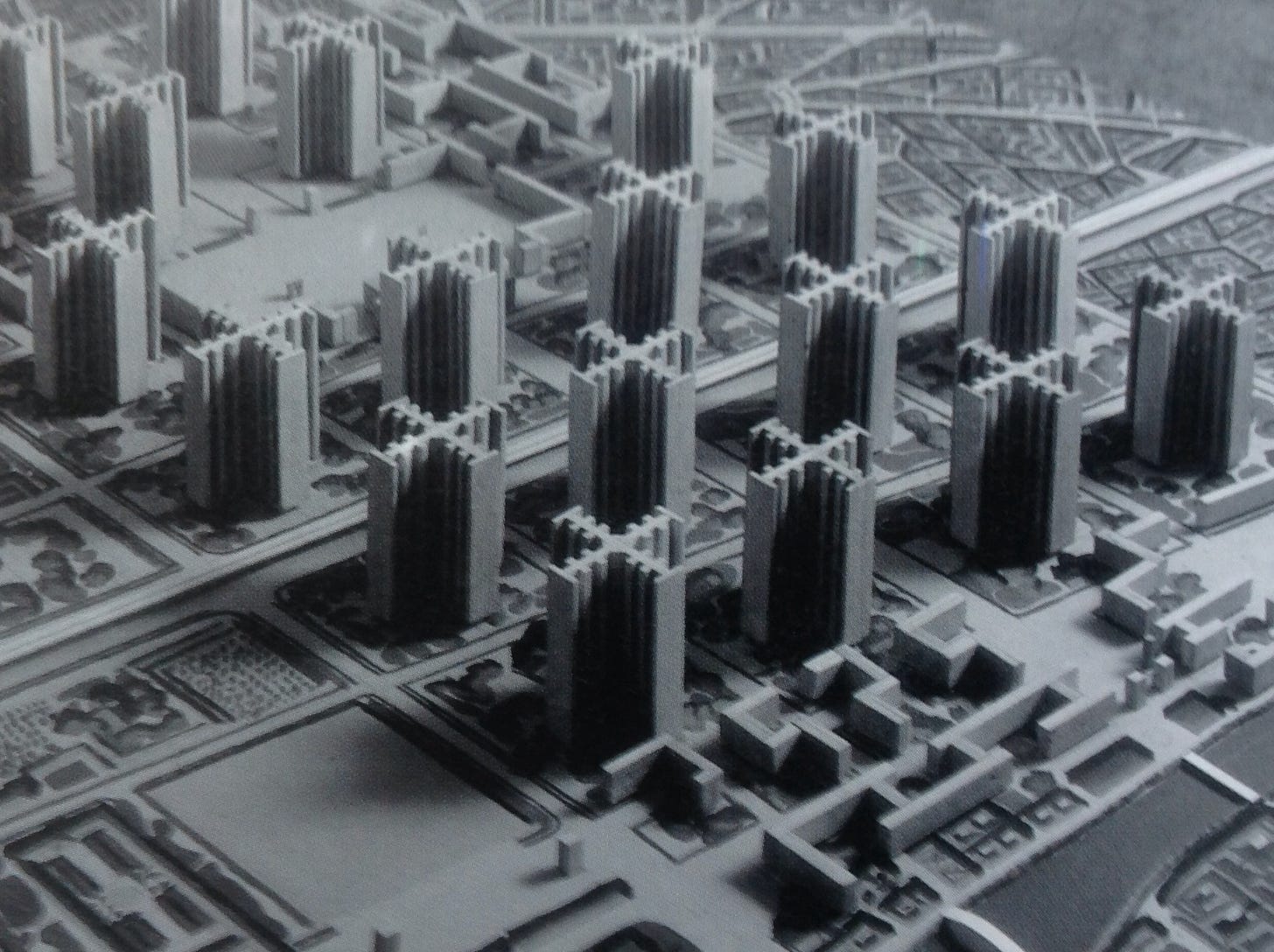

That last example from above, the greening of a large area of Paris, is a particularly famous unrealised proposal. “Le Plan Voisin” was pitched by famed modernist architect Le Corbusier as a response to declining living standards in Paris. Corbusier argued for a cityscape that would have been both more dense, replacing sprawling slums of individual houses with huge, high-rise apartments, and less dense, by setting these vast buildings in the middle of parkland. It was a radical reimagining of what cities could look like, one that placed reducing sprawl and connecting inhabitants with nature at its centre. It was an aspirational notion for the city that described a version of Paris that was entirely unlike any city had ever been. No city building videogame currently in existence would allow you to replicate the concept. Le Corbusier’s understanding of how a city could function, if we simply invested in infrastructure that would allow for it, is too alien to the building blocks of these games. You can't manifest le Plan Voisin in Cities: Skylines because the game, at its core, presupposes the elements and functions of a city in a way that is limited to the kinds of cities that already exist.

For a smaller scale example, let’s look at “modern roundabouts”, a staple of road engineering. What you likely understand to be a roundabout is, in fact, a mid 20th century invention; a product of Britain's post-war infrastructure projects and their national Road Research Laboratory.

Of course, I say you “likely understand”, but if you’re from the United States, there’s a good chance you’ve never actually seen or driven on a roundabout. The reasons for this are complex enough to be an essay in their own right (and indeed, that exists), but for our purposes its enough to know that urban planning in the US by-and-large omits roundabouts in favour of controlled intersections, and this is a philosophical gap that manifests within city builders. So, we have Cities: Skylines, with its European underpinnings, and its many approaches to constructing a variety of modern roundabouts, giving you an invaluable tool for managing traffic in your dream city (modders have even replicated the Magic Roundabout, another mid-century British traffic management experiment). Skylines presents a utopian vision of road engineering, where complex tweaking and rearranging of all manner of intersections, one-way systems and over/underpasses combine to create perfect, high-flow traffic networks. Contrasting this is the SimCity series, rooted in North American (and if we want to get really specific here, Californian inspired) urban philosophies, which since the first game in 1989 has not featured a single roundabout (outside of mods). The 2013 game technically does allow you to build something resembling a “traffic circle”, the precursor to the modern roundabout, and something genuinely found in historic American roading infrastructure, even replicating many of the problems of this design, which rendered it rapidly obsolete and which set the US against further experimentation with traffic circles in their cities.

These two games’ approach to this roading feature illustrates the difference between “prescriptive” and “descriptive” designs. SimCity is prescriptive, it says “this is the way North American cities lay out their roads, so that is how it must be represented in the game”. Skylines is descriptive, it depicts the different component parts that a road network might contain and then allows you to string them together in a way that works for you and your city. There are more subtle ways this difference in approach manifests. Much European roading philosophy centres around limiting speed on smaller roads to create safer, quieter spaces. This is an idea detached from urban density, meaning it might just as likely be found in urban centres as in suburbs. Skylines partly represents this through both its pathing and its noise pollution mechanics. Cims (Skyline’s tongue-in-cheek alternative to “Sims”) don’t want to live on busy roads, and your transport infrastructure needs to account for that. It doesn’t matter whether they’re in high-rise apartments or individual eco-friendly passive-housing. Contrast this with SimCity, where in the 2013 entry density is tied to road size. Want high density urban centres? Well, I hope you like massive six-lane roads. Amusingly, SimCity accidentally ends up reflecting the principle of “induced demand”, where these wider roads immediately fill up with cars and do not solve traffic problems because the same bottlenecks inevitably exist, and suddenly a whole bunch more people want to be in cars.

Even simple mechanics reinforce presuppositions about how cities “have” to be. Up until the latest SimCity, that series worked on a tile-based design, which largely encouraged players to build North American style, regimented urban grids. Setting aside whether this is actually an efficient mode of urban design, urban grids are a hallmark of European colonial urbanism (obviously grids do appear elsewhere in historical urbanism, but the famous contemporary examples are firmly from this category). Urban grids, Pier Aureli argues, are a product of the need for colonies to be able to preplan and apply “predictable order” to colonised places. My favourite example of the foibles generated by arbitrarily laying down grids comes from my hometown of Wellington in Aotearoa. A colonial city, much of central Wellington’s layout follows the traditional colonial grid, laid down by planners from the far side of the world, often ignoring the realities of the local geography. One street in this grid, Dixon St, is split in half by a near vertical cliff. This map (click to enlarge the preview to a high resolution, scrollable map) shows the original colonial grid, including the impossible Dixon Street as well as some other streets of dubious practicality to anyone who knows the hills of the area. Grids are not the only, or even the most common way of laying out cities, yet SimCity has historically limited and even encouraged grids as the fundamental unit of city design.

Ultimately all of these games’ vision of what a city can be is limited by the historical decisions that were made around the cities that the developers looked at when they were conceptualising their games. No matter how creative you are, you are always going to be limited to building cities that work more-or-less the same way as contemporary, predominantly western, urban areas.

Does Any Of This Matter?

Short answer: yes. These games are aspirational. For whole generations they have acted as tools through which to explore and shape our understanding of the ideal city. When those understandings are shaped by prescriptive understandings of society and urbanism we risk reinforcing bad ideas, and some of these bad ideas can be fundamentally limiting or even actively harmful to societies where they take root.

An example of this is how SimCity approaches public transport. In SimCity games, rich Sims will not use public transport, but this reinforces a notion that is not necessarily true. There’s a famous quote from Enrique Peñalosa, a former mayor of Bogotá, that is turning up a lot in online spaces these days: “an advanced city is not one where the poor can get around by car, but one where even the rich use public transportation”. It’s a huge philosophical gulf between SimCity and Cities: Skylines. Wealthy Cims will happily use public transport. This fundamentally shifts the ways that these playerbases view public transport. Skylines players “dream” cities regularly incorporate robust public transport, most expansions for the game include new forms of public transport, and the Mass Transit DLC, which adds a great many ways to centre your urban design around effective public transport, is regarded as the most essential to own. Each of these game series pulls players in different directions as regards the ideal city.

Similarly, Skylines frames services and housing quality as tools for generally improving people’s lot. Providing access to these things only ever leads to a better city for its inhabitants (although Bradley Bereitschaft contests this, suggesting that Skylines ignores the impact of gentrification and instead pushes a neoliberal fantasy about the impact of wealth on cities). SimCity, on the other hand, necessitates that you keep some areas downtrodden in order to create affordable housing for lower income workers. Failure to provide access to suburban slums and tenement districts will grind the regional economy to a halt. Here pleasant housing is reserved for those who have “earned” it.

Beyond this the basic structure of cities is strictly formalised by all of these games. Both SimCity and Cities: Skylines presume roads are necessary, a structure that even pedestrianised cities must by default be structured around. This makes sense as a way of structuring game mechanics. It’s difficult to fault its practicality, but it does limit what your cities can be. Both series also rely on painting single use “zones” to determine where buildings will appear, and of what type they will be. Single use zoning laws are one of the major limiting factors in North American urbanism, one of the major contributors to the US’s out of control urban and suburban sprawl. It makes sense from the perspective of designing a functional, easily learnable game, but it contributes to teaching a whole generation of gamers that this is THE way of laying out cities, which it quite simply is not. Bereitschaft expresses concern that this is an explicit danger; that these games are a gateway for many into urban planning and that they are being exposed to bad assumptions about urbanism.

Of course, these games also do include speculative, progressive science fiction elements that are designed to hypothesise the ways cities of the future might look. SimCity 2000, for example, includes two major science fiction elements which do strive towards a somewhat utopian vision of the future of cities: cheap, clean energy and arcologies.

The powerplants are the simpler to talk about of the two. SimCity 2000 allows you to found a city as early as 1900 and witness various technological innovations as the decades progress. Early powerplants mostly burn fossil fuels, producing large amounts of pollution, potentially reducing land values and upsetting local residents. As years pass better, cleaner ways of producing more and more electricity to fuel your growing metropolis emerge. as you start to move into the “future” (the game was released in 1993 so some of the technological innovations happen in our past) new, cleaner powerplants appear. Microwave powerplants receive electricity beamed from orbiting solar panels, while fusion powerplants generate limitless clean energy with no downsides other than the high cost to buy-in. It’s a thoroughly utopian vision, one that puts trust in the idea that pollution, a great evil in the game’s philosophy, is solvable, soon.

Archologies are slightly more complex. The real world theory behind arcologies proports to solve many of the negative environmental issues created by cities by placing all of the services and infrastructure of a city in a tiny, often vertical, footprint. The idea behind arcologies is that they minimise land use, and reduce pollution by having people work and live in much closer proximity than traditional cities would allow. While the term was coined in the 60s, it’s worth noting that the ideas behind it are reflected in Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin from the 20s. The “Unité d'Habitation” concept argued that individual houses were ecologically ruinous, a waste of resources, and that by building high-rise apartment blocks that could scale-up services, urban design could better exploit the efficiencies of scale.

But the truly great thing about the unité d'habitation concept is that it’s not sci fi. A number were built in response to mid-century Europe’s post-war need for new, efficient housing. The concept is entirely feasible. This might be where SimCity is actually at its most conservative. It pitches solutions that might allow more dense and environmentally friendly cities as being presently unattainable, a technology of the future, when the truth is we’ve known how to achieve this for more-or-less a century at this point.

Does all this mean you shouldn’t enjoy city builders? Of course not. They’re games. Toys to be played with and enjoyed. They operate in a fantasy version of the world where urban renewal and redevelopment can happen overnight, without public consultation or complicated engineering challenges. But you should strive to remember that they are toys. That they do not describe the outer limits of what our cities could look like. That you don’t have to settle for the way things are or have been.

Some Reading

I opened by talking about a bunch of things that projects that never came about, almost all of which are described in Philip Wilkinson’s Phantom Architecture, a fantastic book of insane things that were almost built but never were. It’s well written and, importantly, contains lots of images of concept images and architectural drawings of the things it’s talking about. If you’re interested in exploring some of the “what if” pathways our world could have gone down, this is a great way to do so.

I’d also like to recommend going to your local library and browsing your local history section. Everything where you live, from the parks to the street layouts to the buildings was built for a reason and carries stories, and there’s no better way of beginning to feel connected to the hows and whys of urbanism than by learning to understand the places you see every day. For any of my fellow Kiwi reading this, I’d recommend André Brett and Sam van der Weerden’s Cant Get There From Here – New Zealand Passenger Rail Since 1920, which does a great job describing how the country was prior to the dominance of the car, or one of the many historical photographic collections of various cities, William Main’s Wellington Through A Victorian Lens is a particular favourite of mine.

One day I will put enough time and effort in to learn how traffic works in Cities: Skylines.

As someone with more than a few city builders in my library, it's interesting to see which ones prioritize the things you talk about with different strengths. I'm also finding that others are turning into glorified supply chain systems ("get wood to make planks to make....") which kind of takes out that socialness or spirituality that comes with trying to make a place that people actually live/work/function in.